Our last day for 2018 will be Saturday, 22 December.

We will re-open with some exciting news on Monday, 7 January 2019.

If you need our help before the end of the year, get in touch!

Bookings available online.

Our last day for 2018 will be Saturday, 22 December.

We will re-open with some exciting news on Monday, 7 January 2019.

If you need our help before the end of the year, get in touch!

Bookings available online.

We know the feeling. You’ve been training solidly, competing well and things feel like they’re coming together (finally!).

Until that moment amongst a heated roll, that you lose your base and land smack-bang on the point of your shoulder.

You have an immediate reflexive wince of pain. You feel like someone stuck a knife into the point of your shoulder and your arm ain’t moving very far away from your body.

It definitely doesn’t like you moving the arm across the body and it may even look like a little speed hump at the end of your shoulder.

Welcome to the acromioclavicular joint, the notorious AC joint in contact sports like BJJ. This is the joint that lies between the end of your collarbone and shoulder blade and acts as a strut to stabilise the shoulder/arm complex.

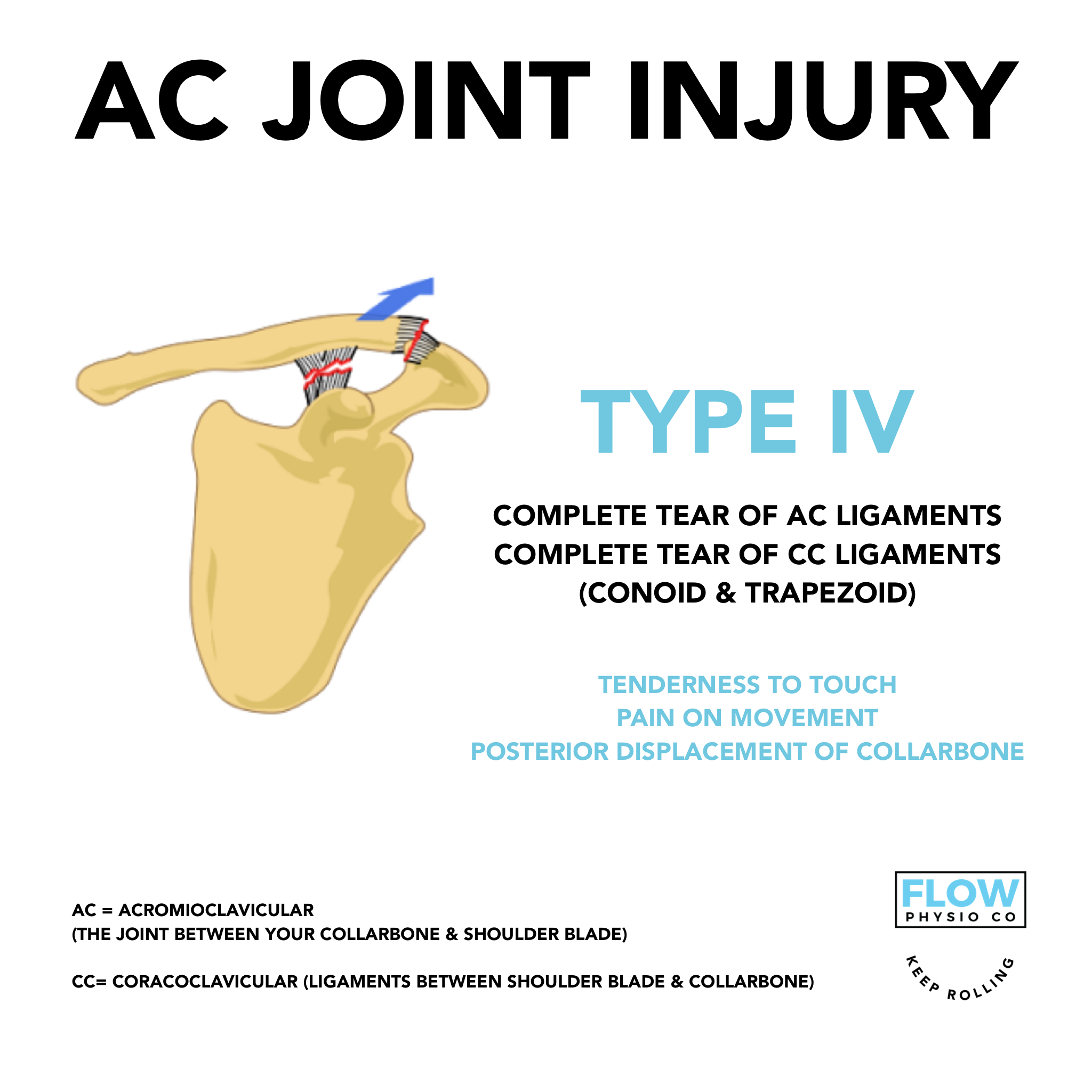

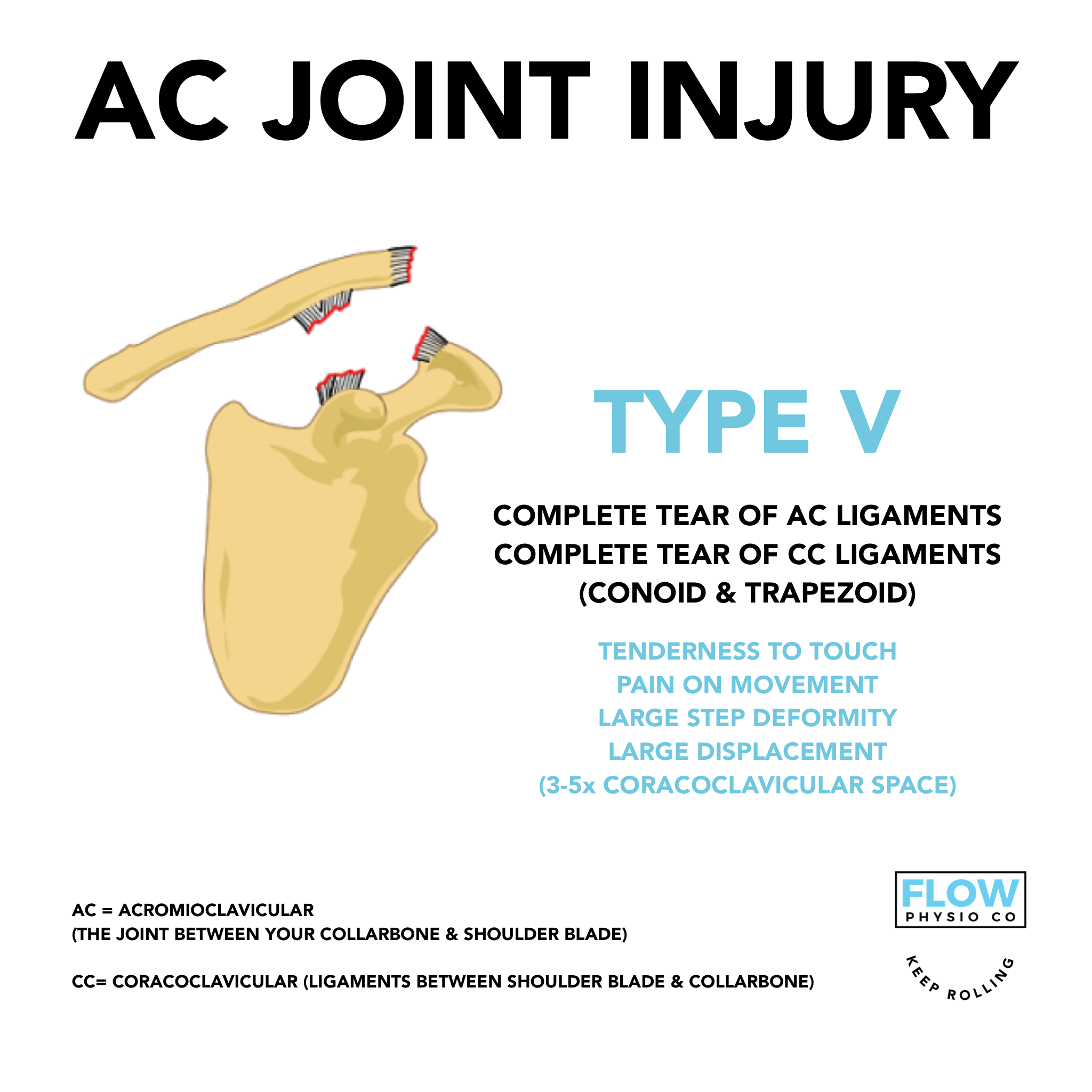

These AC joint injuries are classified into 6 different types according to the commonly used Rockwood Classification:

Management of AC joint injuries follows the general principles of all ligament injuries and will be dependant on the grade (type) and the end goals of the individual.

As a general rule, surgical intervention may be indicated for type 4, 5 and 6 AC joint injuries and type 3 injuries that do not respond to non-surgical management.

Like all injuries, the rehabilitation and exercise or loading exposure will vary from person-to-person. As a general guide, initial management begins immediately and aims to minimise bleeding and swelling and treatment aims to:

promote tissue healing

prevent stiffness

protect from further damage

strengthen shoulder musculature to provide dynamic stability.

Isometric strengthening exercises can be started as soon as pain allows and usually begin close to the body with a progression plan to move away from the body as the body undergoes it’s natural healing response to injury.

We usually look for no AC joint tenderness and full pain-free movement as a starting point for starting the conversation about returning to sport.

We like to see the completion of a full rehabilitation program that focuses on restoring full function and strength of the entire shoulder complex, as well as a graded return to rolling that may involve light drilling and flow rolls initially, with an increase in exposure as the shoulder adapts to the additional stress loads of training.

Full return to training will be individual-specific and criteria driven.

Keep Rolling!

Gym and bootcamp numbers are increasing and it looks as though everyone is now coming out of hibernation. Unfortunately, as a consequence of this we see more people present to the clinic with common complaints related to their new exercise regimes.

One of the most common presentations we see is patellofemoral pain, that is pain arising from the kneecap and its articulation with the femur or thigh bone.

It often presents with the gradual onset of pain and will commonly be aggravated by squatting and lunging motions along with stair-climbing and running, it often settles with rest however, can often cause a dull ache when sitting for extended periods which is known as movie goer’s sign.

We often see people present with an increased load, they have often commenced or increased squatting, lunging and running which can cause aggravation of the patellofemoral joint.

There are a multitude of factors that play varying roles including behavioural, biomechanical/anatomical, technique, muscle imbalances, weakness or restriction.

Here we will cover a general but thorough approach to what is worth looking at in the treatment of patellofemoral pain.

This is about looking upstream and downstream, the patellofemoral joint does not like a rotary component which can be caused by poor lumbopelvic control (what the core/hip is doing) upstream or poor foot biomechanics (what the foot is up to) downstream.

How do the movements look unweighted, weighted and when fatigued?

There is usually a load related component so it is always worth looking at how much you are doing currently vs what you were doing previously and furthermore how to plan the load to ensure it improves. Gradual loading is the best loading (3).

How strong are the glutes and quad muscles as these 2 groups of muscles are shown to be very important when it comes to patellofemoral pain (1-3). Additionally, how strong are the calves, groin, core and hamstrings? If everything is stronger than even better! There is a significant reduction in injury risk with increased strength (4-5).

Are there restrictions elsewhere in the biomechanical chain causing the knees to compensate?

Is there a previous ROM limitation at the ankle due to a previous injury causing the knee to compensate? Is there limitations/tightness in the hamstring or calf? Is there significantly limited thoracic extension causing you to fall forward placing excess strain on the knees during squatting or overhead movements? Is the foot rolling outwards to make up for restricted ankle ROM (1-3)?

Unfortunately, patellofemoral pain is often a very niggly condition and a large number of people experience ongoing issues even with some form of treatment (6). As patellofemoral pain is such a multi-faceted condition it requires a very thorough approach to specifically address all the potential contributing components. It will take time but it is important to be consistent, thorough and methodical in the approach to get best results.

Alignment and control

Lumbopelvic control

Foot mechanics

Technique

Load management

Strength

Range of motion

References

Barton CJ, Lack S, Hemmings S, et al. The ‘Best Practice Guide to Conservative Management of Patellofemoral Pain’: incorporating level 1 evidence with expert clinical reasoning. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:923-934.

Crossley KM, Callaghan MJ, Linschoten RV. Patellofemoral pain. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:247-250.

https://www.mickhughes.physio/single-post/2016/06/21/Patellofemoral-Joint-Pain

Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Jun;48(11):871-7. PubMed PMID: 24100287. Epub 2013/10/09. Eng.

Thomas MJ, Wood L, Selfe J, Peat G. Anterior knee pain in younger adults as a precursor to subsequent patellofemoral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2010;11:201. PubMed PMID: 20828401. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC2944218. Epub 2010/09/11. Eng.

Photo: Peter Hinton (http://hintonzone.smugmug.com) Southern Cross Jiu Jitsu Academy

Craig at Winter Cup 2018 - Sydney Uni

We know the frustration when injuries happen as a consequence of this healthy addiction.

As battling white belts at Flow Physio Co we need any extra edge that we can get.

We like to take a proactive approach aiming to maximise performance and we would like to share this with you to keep you rolling.

With the growing popularity of BJJ and grappling in Sydney and with minimal information available locally, we have decided to put together a series of blog posts, videos and exercises that aim to help you improve performance on the mats and minimise time spent off the mats due to injury.

We understand the time constraints so we want to provide simple research based strategies for you to use.

Today, before we get into talking about specifics on the mats we will discuss three areas to address off the mats that can have a big impact on performance and injury risk.

These are especially important to BJJ but are important to all sport and physical endeavours:

“Sleep is the greatest legal performance enhancing drug that most people are probably neglecting”

- Professor Matthew Walker.

It is generally advised that the optimal sleep duration for adults is 7-9 hours and for adolescents it is 8-10 hours. Sleep can also be supplemented by napping with good effect. (1-2).

Sleep is important for growth hormone release and muscle protein synthesis aka repair, adaptation and growth of muscles and connective tissues. Learning and memories are also consolidated while we sleep.

Studies on athletes have found measurable improvements in athletic performance and skill execution when sleep duration was increased and significant declines in performance with lack of sleep (1-2). Other research has shown significantly higher rates of injury as the hours of sleep per night decrease (3).

In a sport as mentally demanding as it is physically, this can be the difference between submission or having your opponent ending up in full mount.

Strength training has many benefits for athletic performance including:

Increased speed

Agility

Power and efficiency

Reducing injury risk

Strength training alone has been shown to reduce the risk of overuse injuries by 50% and acute/traumatic injuries by 30% in a systematic review of 26 000 participants (4 & 5).

So not only will your game be stronger and more explosive but it will keep you dominating for longer.

Whether you are trying to sneak in an extra couple of classes or have recently had a time off the mats for a well deserved vacation, any spike or drop in the short term vs long term workload can be linked to the likelihood of suffering an injury (6).

Consistency is important; long term high training loads make us more resilient to injury. Therefore, high work loads in themselves are a good thing, as long as we progressively load to that point allowing the body time to recover and adapt (7).

*For those wanting to get a little more technical. Every exercise session you do over the course of a week can be easily measured by multiplying the session time (mins) by a score out of 10 (rate of perceived exertion ie. 0=asleep, 10=max effort) and each session to calculate the weekly total. To reduce the likelihood of injury it is advised to not progress exercise loads by more than 10% per week and remain in the sweet spot of training loads (more on this in a later post) (6).

References:

https://www.mickhughes.physio/single-post/2017/05/26/Sleep-Injury-Performance

Simpson NS, Gibbs EL, Matheson GO. Optimizing sleep to maximize performance: implications and recommendations for elite athletes. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2016 Jul 1. PubMed PMID: 27367265. Epub 2016/07/02. Eng.

Milewski MD, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, Pace JL, Ibrahim DA, Wren TA, et al. Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2014 Mar;34(2):129-33. PubMed PMID: 25028798. Epub 2014/07/17. Eng.

Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Jun;48(11):871-7. PubMed PMID: 24100287. Epub 2013/10/09. Eng.

https://www.mickhughes.physio/single-post/2016/03/27/Load-Management-Part-1-Overuse-or-Underprepared

FIFA 11+ For Kids is a scientifically developed exercise program that aims to reduce the occurrence and severity of injuries in children aged 7-14 years of age. It is recommended the exercises are used as a warm up at every training or game. It aims to be fun for kids but at the same time teaching them fundamental and sport specific motor skills and as a consequence also improves performance.

The program focuses on a number of key areas including:

Spatial orientation, awareness and anticipation, especially while dual tasking to minimise unintended and unexpected contact with other players or objects.

Body stability and movement coordination.

Appropriate fall techniques to minimise consequences of any unavoidable fall or tackle.

A large European randomised controlled trial involving over 4000 kids aged from 7-12 demonstrated approximately a 50% injury reduction in teams that used the FIFA 11+ Kids as a warm up. More specifically match injuries were reduced by 31%, training injuries by 40%, lower extremity injuries by 41%, overall non-contact injuries by 55% and severe injuries by 56% (1).

Typically, there are different injury profiles seen in skeletally mature athletes compared with adolescents and then children. Younger footballers tend to experience more fractures, bone stress and injuries to the upper body and fewer strains and sprains.

Approximately 15-20 minutes once the players are familiar with the exercises and at least twice per week to be effective.

Approximately 10-12 weeks, the key to its success is consistency.

With the football season largely done and dusted for another year, now is the time to plan for the season ahead. By implementing a simple warm up routine many tears and appointments with doctors and physios can be easily avoided in our little footballers.

Sources:

1. https://www.fifamedicinediploma.com/lessons/prevention-fifa11-kids/

2. https://www.fifamedicinediploma.com/wp-content/uploads/cdn/fifa11plus_kids_booklet.pdf

3. Trial to Assess the Efficacy of '11+ Kids': A Warm-Up Programme to Prevent Injuries in Children's Football-https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29273936-A Multinational Cluster Randomised

4. A new injury prevention programme for children's football--FIFA 11+ Kids--can improve motor performance: a cluster-randomised controlled trial-https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26508531